BY JACOBO RAMÍREZ

Governments and businesses argue that the energy transition contributes to sustainable development and environmental conservation. And yet the confrontation between corporations and the state with Indigenous Peoples reflects a continuing oppression and repression. Discussions on self-determination, respect for human rights, and investment in climate change mitigation are woven together in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec to offer new insights into the conflicts and social unrest created by the green industry.

In September 2013, I set out to undertake fieldwork in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, in the south of Mexico. Before embarking on the four-hour road trip from Tuxtla Gutierrez, the capital of Chiapas, I received some advice for the trip: “Don’t drive after dark, don’t stop in isolated places, and don’t ask for help from the local police.”

I was on an isolated and windy road still some 45 minutes from Juchitán when darkness began to descend. I started to feel anxious that something bad might happen. I thought back to the murders I had read about. Some had taken place on this very same road, alongside the wind farms.

I particularly recalled Héctor Regalado Jiménez, a member of the Popular Assembly of the Juchitec People (APPJ), who had been murdered a few months earlier for protesting against the construction of the Bii Hioxho wind farm, owned by the Spanish company Gas Natural Fenosa, now Naturgy. The Juchitec fisherman was shot six times by hitmen accompanied by local police. Incredibly, no one has ever been arrested for or charged with this crime, clearly illustrating the reigning lawlessness in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and the impunity of those involved.

I soon reached the top of a hill. From there you could see the bright red flashing lights of the wind turbines. It felt as if I was in some kind of science fiction movie. This image of a futuristic city gradually changed, however, as I approached the wind farms: unpaved roads, candlelit houses and crossroads with no traffic lights were all indications of a continuing internal colonialism.

Proliferation of wind farms and disputes between communities

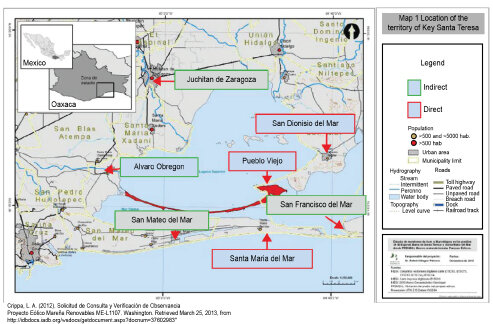

Due to its geographical location as a connecting point between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, the Isthmus of Tehuantepec has long been a source of geopolitical dispute, ever since colonial times. Residents often tell of divisions between the different Indigenous communities that inhabit the territory: Zapotec, Ikoot, Chontal, Mixe and Zoque. In recent years, ethnic bids have been made for wind investments in their territories: the wind corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec is one of the best wind resources in the world.

Members of pro-investment communities are called “pro-wind” and support these projects, provided the developers offer them benefits in return: free access to medical check-ups, cash payments and materials to build their homes. One local resident commented on the community divisions: “Some people have leased their land but I don’t know how much they are paid. It’s all very hush hush. Now, they’ve become hamaqueros: they don’t farm, they don’t fish, they don’t trade; they just sleep in their hammocks and await the monthly payments from the companies.” In contrast, the “anti-wind” communities receive neither payments for renting their land nor the in-kind benefits mentioned above.

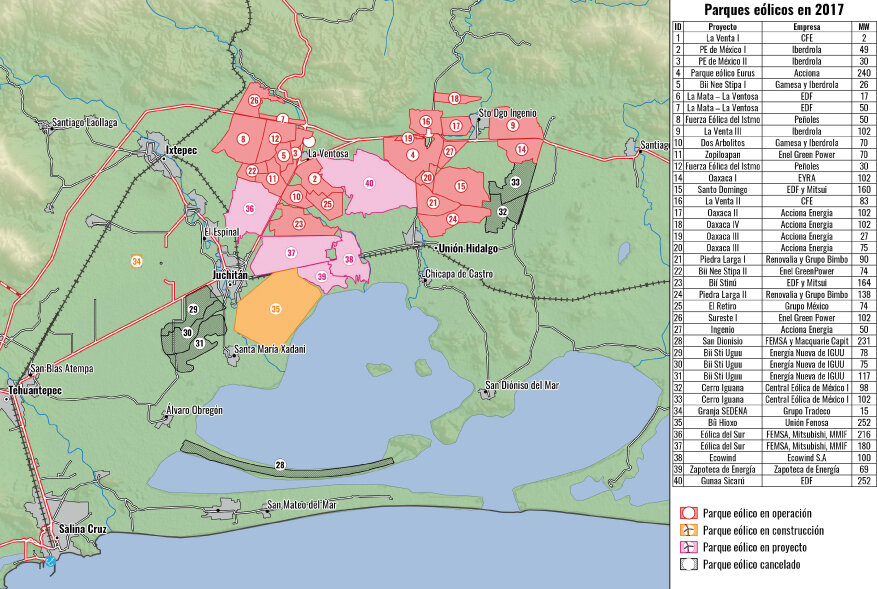

The establishment of the first experimental mini wind farm in 1994 in the community of La Ventosa, with a capacity of 1.5 MW generated by seven Vestas turbines of 225 KW each, led many to believe that development had finally arrived. And yet, according to the Zapotec, what arrived in reality were investments that led to a colonial-type exploitation and the grabbing of Indigenous Peoples’ lands. As of January 2020, 1,600 wind turbines had been installed in 32 wind farms across the territory.

Burgeoning wind investment in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec is a result of the Mexican government’s policy of transforming its energy matrix to meet its commitments made under the Paris Climate Agreement. For the past 30 years, Mexico has been governed by parties of the centre-right: the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) and the National Action Party (PAN). A new party, the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA), Mexico’s hope, swept the 2018 elections, however, and President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, better known as AMLO, embarked on an energy agenda unlike that of any previous administration (and in particular contrast to the 2013 Energy Reform).

“Burgeoning wind investment in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec is a result of the Mexican government’s policy of transforming its energy matrix to meet its commitments made under the Paris Climate Agreement.”

AMLO has cancelled public auctions of renewable energies in order to encourage traditional energy sources such as oil, gas or hydroelectricity. He justifies these measures on the basis of the Policy of Reliability, Security, Continuity and Quality of the National Electrical System, as well as in terms of protecting Indigenous Peoples due to the human rights abuses caused by foreign direct investment. In 2018, the Indigenous Peoples, both pro and anti-wind power, applauded the federal government’s energy reforms. One Indigenous man in favour of the wind parks commented: “The changes proposed by AMLO are good because they will allow us to review all the abusive contracts (such as the rent paid for land on which to build the wind farms) that we have signed through ignorance”.

In October 2020, anti-wind protesters such as those from Unión Hidalgo municipality filed a civil suit in the Paris Courts against Electricité de France for violation of their human rights during the free, prior, and informed consultation for the installation of the Gunaa Sicarú wind farm. To date, neither the contracts signed by the pro-wind communities nor the demands made by the rights defenders have been reviewed.

Indigenous Peoples’ struggles for survival on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec offer a clear illustration of the historic perpetuation of inequality and abuses of power. This situation stands in stark contrast with Mexican governments’ efforts to meet their climate change commitments and achieve the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. At the same time, neither centre-right nor left-wing governments such as AMLO’s have made efforts to ensure the autonomy, self-determination and survival of Indigenous Peoples.

A commitment carried on the wind

This large-scale investment in wind energy on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec has only deepened the unequal development that directly affects Indigenous Peoples. Governments and the green energy industry have rediscovered Indigenous territories: investment in supposedly forgotten, backward and unproductive lands are now allowing them to demonstrate their “commitment” to fighting climate change.

For this reason, coordination between Indigenous struggles for autonomy is of particular importance to counter domination and exploitation, and to enrich democratic alternatives. A member of the resistance group in San Mateo del Mar says, “The companies are going to kill our communities because of the divisions that are emerging in our region.”

“Coordination between Indigenous struggles for autonomy is of particular importance to counter domination and exploitation”

Anti-wind resistance groups are mobilising against the environmental and geographical changes taking place on their territories but they are being challenged by associations opposed to AMLO’s administration and in favour of the wind farms. Such is the case of Renovable x México, which is promoting investment in renewable energy. It justifies it with regional development and climate change mitigation but ignores the prior consultation processes and human rights of Indigenous Peoples that are enshrined in Mexican legislation and international conventions.

These dynamics appear to pose a post-colonial ethical contradiction: Indigenous cultures are recognised in Mexico but, at the same time, these peoples are subjected to environmental and geographical injustices on their own territories. Economic reforms and the energy transition, along with the rhetoric of the war on climate change, have given renewed value to the Indigenous territories. In Mexico, the privatisation of communal lands has resulted in a geographic and social debt, forcibly displacing Indigenous Peoples and threatening their way of life.

“Economic reforms and the energy transition, along with the rhetoric of the war on climate change, have given renewed value to the Indigenous territories.”

There seems to be no constructive dialogue in Mexico to ensure that Indigenous Peoples’ right to self-determination is respected alongside the start of the energy transition. Free, prior and informed consultation, a mechanism for popular participation in investments that affect Indigenous Peoples, appears little more than a simple formality on the part of governments and businesses. They can thus claim to have fulfilled a requirement of the Electrical Industry Law enacted in 2014.

While Mexico has made great efforts to establish regulations governing free, prior and informed consultations, such consultations on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec do not comply with current legislation, and nor did such attempts prior to the Energy Reform comply with ILO Convention 169, ratified by the country in 1990.

Wind energy as a perpetuation of internal colonialism

Indigenous Peoples’ visions of development on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec are based on pride in their history of struggle to obtain access to education, health, drinking water and electricity, as well as respect for their right to self-determination. And yet they share a position of subordination within a system of inequality that has been in place since European colonisation. In this sense, wind farms on Indigenous territories threaten local traditional economies, transform the local geography, and encourage human rights abuses.

These outcomes suggest that the aim of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through investment in wind energy is naïve due to a failure to adequately consider the socio-economic traditions of the Indigenous Peoples. Equal access to renewable energies and recognition of and participation in the use of geographical spaces are at the heart of Indigenous debates around the problems that arise from investment in renewable energies.

“Wind farms threaten local traditional economies, transform the local geography, and encourage human rights abuses.”

In turn, struggles for rights are more challenging when these demands threaten economic interests and the discourse on SDGs. Such is the case for SDG 13, for example, which calls for urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts. Investments in renewable energy could offer an alternative in the transition to clean energy and ensure access to affordable, safe, sustainable and modern energy for all.

When investments in renewable energy violate human rights such as peace and justice, however, the state and businesses have a duty of creativity and innovation in order to protect and guarantee the fulfilment of these rights for Indigenous Peoples living in vulnerable conditions. Otherwise, the discourse of climate change mitigation will be no more than empty rhetoric perpetuating internal colonialism through investment in wind.

Jacobo Ramírez is Assistant Professor at Copenhagen Business School (CBS). The conclusions and recommendations above do not necessarily reflect the views of those organisations mentioned.

Source: Debates Indigenas

0 Comments